Like many of the increasing number of non-religious in Australia, I was outraged when I first learned that ‘religion and theology’ are considered fields where individuals have “critical skills” that could see them granted an exemption from the general ban on non-citizens entering Australia as part of our COVID-19 border restrictions.

The federal government has been highly critical of state governments that have closed their borders, but its own border policy is no less hard-line. Its COVID-19 travel restrictions state that “Australia has strict border measures in place to protect the health of the Australian community” and include this blunt warning: “You cannot come to Australia unless you are in an exempt category or you have been granted an individual exemption.”

Exempt categories include Australian citizens or permanent residents and their immediate family members, New Zealanders ordinarily resident in Australia, airline crew, diplomats, or those just passing through. But if you’re a non-citizen, you are pretty much shut out. That is unless you’re a priest. Or a rabbi. Or a pastor.

Also on The Big Smoke

- God give us strength: Morrison’s faith is a national problem

- 11 ways to fix the maligned Religious Discrimination Bill

- The bible truth: Non-religious Australians a second class under Morrison

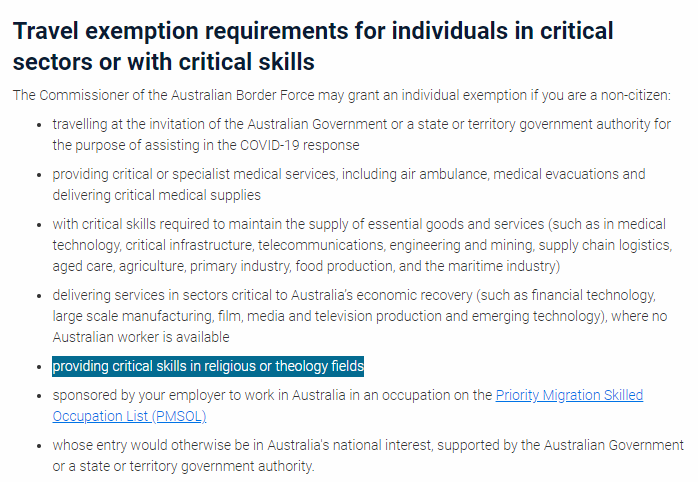

The federal government’s new COVID-19 travel guidelines, published on 4 September, state that the Australian Border Force Commissioner can grant travel exemptions to non-citizens if they work in critical sectors or have critical skills. Exemptions for non-citizens can be granted for people invited by a government to help with the COVID-19 response, or people providing specialist medical services, or people who can help maintain the supply of essential goods and services, or people who can help with our economic recovery.

But religion and theology? What “critical” skills might religious functionaries have that merit a travel exemption?

The Home Affairs website

Australia is a secular country but its form of secularism is not like that of France, which opts for complete removal of religion from the public sphere. Australia’s secularism is one of ‘religious pluralism‘, where the state does not endorse one religion at the expense of other religions or of no religion. Our constitution guarantees freedom of religion.

Section 116 states that the Commonwealth of Australia may not “prohibit the free exercise of religion”. If the federal government banned religious functionaries from travelling to Australia, as France might do, arguably it would have to demonstrate that such a measure was not disproportionate to the fundamental right to freedom of religion provided for in s116.

Rather than deliberately privileging religion, as this travel ban exemption appears to do, perhaps the government is just taking a risk-averse approach ensuring it avoids any potential constitutional challenge to its travel ban policy.

In any case, how many religious functionaries are likely to apply for a travel ban exemption?

The Royal Commission into Child Sexual Abuse heard that Australian-born priests make up only half the 1300 full-time Catholic priests working today, with priests from West Africa, India, the Philippines and Vietnam “filling the vacuum caused by the dramatic decline in the number of local priests”. Many Australian-born priests will reach retirement age (75) over the next few years, leaving fewer than 400 in active ministry. The situation is similar, though not as dire, in the Anglican church. In 2019, there were “senior vacancies” in 30 of the 270 churches of the Sydney and Wollongong dioceses, at a time when “Christianity no longer seems respectable in the wider society”.

We know that Australians are leaving institutionalised religion in droves. In just over 12 years, Catholic affiliation has dropped from 28% to 21%, Anglican from 21% to 15%, and Uniting/Methodist from 8% to 4%. Respect for religious leaders has plummeted in the wake of the Royal Commission, and mainstream religious folk have voted in favour of hot button issues like same-sex marriage and voluntary assisted dying in spite of the protestations of their clerical leaders.

All this goes to show that religiosity in Australia is declining and institutionalised religion may be unsustainable in the longer term.

That the federal government may grant a few travel exemptions for priests or pastors coming into Australia to fill long term vacancies is not so much a cause for anguish as a reason for confidence: that the good sense of Australians is slowly but surely rejecting old tribal loyalties and embracing instead the commonsense world of the non-religious.