The following article was first aired (in abridged form) at the 63rd Rationalist Society conference in April 2000 at Box Hill. The topic was “Spirituality without Religion”. It was then published in issue 54 of the Australian Rationalist journal, Winter 2000.

In April 2015, a rabbi happened to read it and sent the following message:

I was on the web, trying to recall the signs of a mystical experience. And, one page led me to you. I thank you for what you do. (I am ordained as a rabbi, but deeply, and publicly, am foremost committed to being a rational, humanist.)Blessings on your work. Rb.

First a word about the topic of the conference as a whole – “spirituality without religion”. Take religion. Why would anybody want to reject religion as a meaningful part of their lives, whether or not the beliefs of that religion can be asserted to be true, when many studies have shown that subjective feelings of happiness and satisfaction in life are highly correlated with religious belief. The facts are pretty unequivocal – religious people are on the whole happier than non-religious people. For the atheist apparently, life’s a bitch and then you die! So why are we all here? Why aren’t we all at the Synagogue today or getting ready to go to Church tomorrow?

If we want to be happy little vegemites we shouldn’t even be congregating here wondering if we can have spirituality without religion, we should be embracing the whole religious system.

Be that as it may, many people today cannot accept any more as literal truths the main tenets of the traditional religions – for example:

- that god is a person, and usually male,

- that god chose the Jewish people and gave them Palestine (you’d think if he really liked them he would have given them Bali or at least Majorca),

- that god lives in a high place called heaven,

- that if we are good, when we die our bodies will be resurrected and we will live there with him , or

- that if we have been bad we will either go to a place of eternal punishment or else be reincarnated as a lower form of life, such as a cockroach or a liberal politician,

- that only males can go to heaven, where all their needs will be tended to by beautiful maidens called houris,

- and so on.

Yet many of these same people who reject religious belief still feel that there is a deeper dimension to life, some kind of, for want of a better word, ‘spiritual’ presence in the universe. Often this sense of the numinous, as Philip Adams perhaps somewhat inaccurately labels it, derives directly from what I have called here, again for want of a better word, a ‘religious experience’ – an experience which is too compelling to be rejected out of hand as a mere aberration. [I shall say shortly exactly what I have in mind by the term ‘religious experience’. ]

For many people, even some who are atheists or agnostics, such ‘religious experiences’ invite, almost demand, a more sympathetic, detailed and extended response than knee- jerk materialist reductionism would allow them. So the questions I hope to explore, if not definitively answer, in this paper are: What is an open-minded but sceptical rationalist to make of this spiritual impulse? How can it be integrated into an atheist world view? And most importantly, what are its implications for how we live our lives?

What I am referring to when I talk about a religious experience are those experiences that have been called by a wide variety of names – higher consciousness, the mystical, the numinous, peak experience, altered state of consciousness, awakening, satori, samadhi, nirvana, cosmic consciousness, and so on. I don’t want to get into a discussion of terminology here, apart from noticing the positive evaluation built in to many of these appellations. I acknowledge that many of these names have specific nuances of meaning within particular cultures but I don’t want to get into semantics and I want to be as inclusive a possible in considering a wide range of similar experiences. Nor am I claiming that such experiences are the only kind of experiences that might be described as religious. The use of the epithet ‘religious experience’ juxtaposed as it was with ‘atheist’ in the title of this talk was designed to be provocative rather than accurate.

From now on I will try to be more accurate, without I hope being less provocative.

It is worth noting at this point that one of the most common characteristics of mystical experiences, as reported by their experiencers [or is it experiencees?] is that they are ineffable, unable to be put into words, incapable of accurate description. So it is perhaps surprising that there are so many descriptions of them about in the literature. It would seem that people who have these experiences are unable to shut up about them while at the same time maintaining that nothing they say does any justice to what they are talking about. But this may be being unfair because if these experiences are as common as it appears then there must be many more people around who have had the experience but have not spoken out.

If the mystical experience is indeed ineffable, perhaps we should stop here and go to lunch. We could take comfort in the words of the Chinese classic, the Dao De Jing – The Book of the Way and its Virtue – which begins:

The way that can be spoken of Is not the true way;

The name that can be named Is not the constant name.

Dao De Jing, Book One I, 1 (Penguin translation)

and later on states:

One who knows does not speak; one who speaks does not know.

Dao De Jing, Book Two, LVI, 128 (Penguin translation)

Or, in the words of the ancient Indian text, the Kena Upanishad:

He who says that Brahman [Spirit] is not known, knows truly; he who claims that he knows, knows nothing.

But like the character in the famous Monty Python sketch you have all paid your money and you are expecting a day and a half of discussion, if not argument, and there are three more speakers to go so we had better press on.

Examples of ‘religious’ experiences

Here are some typical examples of what I am calling here ‘religious’ or ‘mystical’ experiences:

1. One person who thought he knew, but did not speak, at least about his mystical experience was the seventeenth century French scientist and writer Blaise Pascal. The following inscription was on a scrap of paper found, after he died, sewn up in the lining of his doublet:

From about half past ten in the evening to about half an hour after midnight.

Fire.

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob, Not the God of the philosophers and scholars. Absolute certainty: Beyond reason. Joy. Peace.

Forgetfulness of the world and everything but God. The world has not known thee, but I have known thee.

Joy! joy! Joy! tears of joy!

2. Mystical experiences can often be triggered by the beauty or grandeur of nature. This is what happened to the great Indian poet and Nobel Laureate for Literature Rabindranath Tagore as he watched a sunset:

As I was watching it, suddenly, in a moment, a veil seemed to be lifted from my eyes. I found the world wrapped in an inexpressible glory with its waves of joy and beauty bursting and breaking on all sides. The thick cloud of sorrow that lay on my heart in many folds was pierced through and through by the light of the world, which was everywhere radiant.

There was nothing and no one whom I did not love at that moment.

Rabindranath Tagore as reported in a letter to his friend C. F. Andrews

3. But it is not just poets that have these experiences. John Buchan, later to become an intelligence officer in World War I, the author most famously of The Thirty-Nine Steps and eventually Governor-General of Canada, was farming out on the South African veldt when he had this experience:

Next morning I bathed in one of the Malmani pools – and icy cold it was – and then basked in the early sunshine while breakfast was cooking. The water made a pleasant music, and near was a covert of willows filled with singing birds. Then and there came on me the hour of revelation, when, though savagely hungry, I forgot about breakfast. Scents, sights, and sounds blended into a harmony so perfect it transcended human expression, even human thought. It was like a glimpse of the peace of eternity.

John Buchan. Memory Hold-the-Door.

4. Although it seems easy to have ecstatic thoughts when confronted with something of utter beauty, perhaps the real test is if you can have a spiritual experience arising out of the mundane or the ugly. It is entirely plausible that someone might be able, like William Blake,

To see a World in a Grain of Sand And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

William Blake. Auguries of Innocence

but can someone see a world in a plastic bag or heaven in a toxic chemical dump?

Something like this happens in one of the most interesting recent Hollywood films, the Academy Award winning American Beauty. The disturbed and disturbing American teenager Ricky offers to show his girlfriend Jane “the most beautiful thing I have ever filmed”. The video image he is refering to is of an old plastic bag blowing about in the wind, and Ricky says:

It was one of those days when it’s a minute away from snowing. And there’s this electricity in the air, you can almost hear it, right? And this bag was just … dancing with me. Like a little kid begging me to play with it. For fifteen minutes. That’s the day I realised that there was this entire life behind things, and this incredibly benevolent force that wanted me to know there was no reason to be afraid. Ever.

…

Sometimes there’s so much beauty in the world I feel like I can’t take it … and my heart’s going to cave in.

Alan Ball. American Beauty: The Shooting Script

These words are echoed by the film’s hero, Lester, in the final scene of the film, although it’s interesting to note that while Ricky’s heart was going to cave in, Lester’s is going to explode:

… it’s hard to stay mad when there’s so much beauty in the world. sometimes I feel like I’m seeing it all at once, and it’s too much, my heart fills up like a balloon that’s about to burst … and then I remember to relax, and stop trying to hold on to it, and then it flows through me like rain and I can’t feel anything but gratitude for every single moment of my stupid little life …

Alan Ball. American Beauty: The Shooting Script

This is a truly profound film, although its profundity is so subtly woven into the narrative fabric that it went over the heads of many people. He who has eyes to see.

5. Sometimes mystical experiences occur at times of great hardship or distress. Winifred Holtby, the English novelist, editor and feminist, was at the height of her powers at thirty three when she was told she had only two years to live. Weak, unable to work, tired and dispirited, one day she was walking up a hill when she came to a water trough whose surface had frozen over, and there were a number of thirsty lambs gathered around it:

She broke the ice for them with her stick, and as she did so heard a voice within her saying ‘Having nothing, yet possessing all things’. It was so distinct that she looked around startled, but she was alone with the lambs on the top of the hill. Suddenly, in a flash, the grief, the bitterness, the sense of frustration disappeared; all desire to possess power and glory for herself vanished away, and never came back. … The moment of ‘conversion’ … she said with tears in her eyes, was the supreme spiritual experience of her life.

Winifred Holtby as told to Vera Brittain: Testament of Friendship.

6. Sometimes the experience can come after many years of religious discipline, as is the case with Zen Zen means ‘meditation’, so Zen Buddhism means simply ‘meditation Buddhism’ and the most common form of meditation practiced is ‘za zen’ – sitting meditation. The ultimate aim of this meditation is ‘satori’ – awakening or enlightenment, but such enlightenment is not easily come by. It is seen as the result of a long period of training and practice, as Shui’chi Kitahara, a Japanese Zen practitioner, explains in his imperfect English:

In the morning of the fifth day, I got up at five and began to sit. I returned to the state of the previous night. And unexpectedly soon a conversion came. In less than ten minutes I reached a wonderful state of mind. It was quite different from any which I had experienced in sie za [sitting quietly] or other practices. It was a state of mind, uncomparably quiet, clear and serene, without any obstruction. I gazed it. Entering this state of mind, I was filled with the feeling of appreciation, beyond usual joy, … and tears began to flow from closed eyes. … a state of mind of forgiving all, sympathising all, and further free from all bondages.

Shui’chi Kitahara. Psychologia, 6, 1963.

7. Sometimes the experience can be the actual genesis of a religious life:

I felt a great inexplicable joy, a joy so powerful that I could not restrain it, but had to break into song, a mighty song, with only room for the one word: joy, joy! … And then in the midst of such a fit of mysterious and overwhelming delight I became a shaman, not knowing myself how it came about. But I was a shaman. I could see and hear in a totally different way. I had gained my … enlightenment.

An Inuit shaman. Reported in Knud Rasmussen: The Intellectual Culture of the Iglulik Eskimos.

These are the words of an Canadian Inuit describing how he came to be a shaman for his tribe.

8. Sometimes the experience just comes on someone without warning, as in this experience described by William James:

But as I turned and was about to take a seat by the fire, … the Holy Spirit descended upon me in a manner that seemed to go through me, body and soul. I could feel the impression, like a wave of electricity, going through and through me. Indeed, it seemed to come in waves and waves of liquid love … it seemed to fan me like immense wings.

No words can express the wonderful love that was shed abroad in my heart. I wept aloud with joy and love; and I do not know but I should say I literally bellowed out the unutterable gushings of my heart. These waves came over me, and over me, and over me, one after the other.

William James. The Varieties of Religious Experience.

Experiences of this kind are not as uncommon as is sometimes believed. A survey in 1973 by Erika Bourguinon of the ethnographic literature on 488 societies world-wide found that 437 of them (just under 90%) had one or more institutionalised, culturally patterned forms of altered states of consciousness. And various general surveys of western societies, such as the Gallup Poll, have reported between 43 and 76 percent of adults having such mystical experiences. One of the interesting findings is that very few children have them. They seem mainly to affect adults.

Interpreting ‘religious’ experience

Now it is very important, in examining these experiences to distinguish between the experience itself and the cultural baggage in which it comes wrapped. There is no such thing as a raw experience. All our experiences are mediated by our mental apparatus. This was pointed out early last century by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the great Indian philosopher, who was also President of his country from 1962 to 1967. In his very influential book An Idealist View of Life (1932) he wrote:

In the utterances of the seers, we have to distinguish the given and the interpreted elements. What is regarded as immediately given may be the product of inference. Immediacy does not mean absence of psychological mediation, but only non-mediation by conscious thought. Ideas which seem to come to us with compelling force, without any mediate intellectual process of which we are aware, are generally the results of previous training in traditions imparted to us in earlier years.

Radhakrishnan, p 77.

Which explains of course why Hindus don’t have visions of the Virgin Mary and Christians don’t have visions of the Buddha.

Something is directly experienced but it is unconsciously interpreted in the terms of the tradition in which the individual is trained. The frame of reference which each individual adopts is determined by hereditary and culture.

Radhakrishnan, p 78.

Radhakrishnan adds:

Among the religious teachers of the world, Buddha is marked out as the one who admitted the reality of the religious experience and yet refused to interpret it as a revelation of anything beyond itself. For him the view that the experience gives us direct contact with God is an interpretation and not an immediate datum. Buddha gives us a report of the experience rather than an interpretation of it, though strictly speaking there are no experiences which we do not interpret.

Radhakrishnan, p 78.

And there of course is the rub – ‘strictly speaking there are no experiences which we do not interpret’. If we are to get to the bottom of this mystical experience business we must start speaking strictly. It does make a huge difference if there are in fact ‘no experiences which we do not interpret’ – but more of that later.

Can we say anything about the experiential core of such experiences. Attempts to do this are not new. In fact one of the most comprehensive and still classic investigations was by one of the founding fathers of psychology, William James, in his The Varieties of Religious Experience: a Study in Human Nature (1902). James singled out four main characteristics of these experiences.

Ineffability of ‘religious’ experience

One of course was ineffability, of which we have already spoken. Mystical states are so different from our ordinary states of consciousness that it is difficult to convey in their import and grandeur to another person. For this reason much mystical literature is filled with paradox, symbolism and metaphor. Because the experiences are individual and private, we have no common language with which to talk about them. The unknown is described in terms of the known. Experiencers have no recourse but to resort to symbolic and metaphorical language to describe such things as the mystical union with god or the universe typical of these experiences.

THE MYSTICAL UNION MAY BE SYMBOLISED BY THE MELDING OF INANIMATE OBJECTS OR MATERIALS, for example:

- the individual is the spark or the wood or the wax or the iron that is burnt or melted or tempered in the fire of god,

- the individual is the soil that is dissolved in the water of god,

- the individual is the river which flows into and is absorbed by the ocean of god;

THE MYSTICAL UNION MAY BE SYMBOLISED BY THE WAY THE BODY APPROPRIATES NATURAL ELEMENTS, for example:

- seeing the light,

- receiving the breath of the spirit (the word spirit is itself deeply metaphorical, coming of course from the Latin spiritus meaning ‘breath’),

- imbibing of food and drink, usually, water, milk, fish, bread or wine (“Take, eat; this is my Body which is given for you; … Drink ye all of this; for this is my blood … which is shed for you … “);

THE MYSTICAL UNION MAY BE SYMBOLISED BY HUMAN RELATIONSHIPS

- father/son,

- wife/husband (‘Brides of Christ’),

- lover/loved one (as in the poems of the Sufi mystic, Rumi)

Now the danger here is that the symbolic or metaphorical nature of this religious language can be forgotten and the words can be taken literally. The wafer of bread becomes literally the body of Jesus (which bit, one might well wonder), the wine is transubstantiated into the real blood of Jesus, heaven is literally ‘up there’ and Jesus himself literally ascended to heaven by being bodily lifted into the air. Mythologist Joseph Campbell is fond of pointing out that if Jesus literally ascended bodily into the heavens, even if he was travelling at the speed of light, the fastest possible speed, he could not have got even out of the Milky Way yet, a mere 1,967 years later, because our Galaxy is more than 100,000 light years across.

Campbell believes that this mistake, of taking symbols and metaphors literally, infects particularly the Judeo-Christian religions including Islam. He recounts how a Jewish friend of his staying in a hotel in Guatemala mentioned to the local chambermaid that she came from Jerusalem. “What!” said the maid. “You are from the sky?” Campbell points out that this is one common misinterpretation of the symbol of the promised land, that it is a place in the sky. The other common misinterpretation is that it’s a piece of real estate in the Middle East. “The Christian tradition has one mistake, the Hebrew tradition has the other. ”

The mistaken literalisation and reification of religious symbols and metaphors is something that does not occur so readily in Eastern and indigenous traditions.

Campbell cites the old Sioux medicine man, Black Elk, who described how in his imagination he had pictured himself having a mystical vision on the central mountain of the world, which in his view was nowhere near Jerusalem, but Harney Peak in the Black Hills of South Dakota, but then Black Elk shows a more sophisticated understanding of the nature of religious language than some Jewish and Christian theologians, because he adds decisively: “But anywhere is the centre of the world. ” He knew it was not a geographical location but a symbol.

So one of the difficulties in understanding the experiences of the mystics is in untangling the underlying nature of the experience, if any, from the symbolic and metaphorical language in which it is necessarily expressed.

Passivity of ‘religious’ experience

The second aspect of these experiences cited by William James is passivity. The experiencer, or in this case undoubtedly the experiencee, feels swept up and held by a superior power. Now this is certainly true of most Western experiencees – firstly the experience is something that happens to them, not something they do, and secondly, it is so huge, awesome and overwhelming that it is assumed it cannot come just from inside them but must come, not from just any outside source, but from a very powerful outside source at that. But Westerners come from a tradition which emphasises a transcendental deity and it may be that this idea of god as outside the physical universe predisposes them to interpret their experience in this way.

By contrast, in many Eastern traditions god is seen as immanent in the universe and in particular in human beings, so there is no contradiction between seeing the experience as both part of oneself and divine at the same time. Also in these traditions there is often a conscious attempt to reach such states through techniques such as meditation, yoga and various other rituals and regimens. So in these cases the experience may seem more like an achievement of the individual than a visitation from outside forces.

Although in most of these traditions it is commonplace to point out that “trying to achieve enlightenment” is a surefire method of not doing so.

The passivity is often accompanied, according to James, by sensations of separation from bodily consciousness, disembodied feelings which have now come to be called OBEs – Out-of-Body Experiences. In considering the significance of OBEs it is necessary to say something more about human perception.

The perceptual system

We all know the old saying “Seeing is believing” and we all place a huge amount of reliance on our sense of sight to give us accurate information about our environment. Most of the time this confidence is warranted but not because “seeing” is in fact “believing”. In actual fact “Believing is seeing”, while not entirely accurate either, is at least much closer to the truth than its converse.

There are many experiments that demonstrate the primacy of the mind over the eyes. For example, when subjects in a dark room are told a stationary point of light is moving and spelling out a word, they will see it move and spell out a word.

We tend to imagine that we are like movie cameras, looking out through the lenses of our eyes, receiving a more or less accurate visual impression of our environment directly onto the film stock of our minds, images we then apprehend as our visual field. In the words of Christopher Isherwood in Goodbye to Berlin: “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive. ” We think that what we get is precisely what we see.

However we now know that this is not the case. We are more like television cameras than movie cameras. A television camera samples the information from the light rays coming through the lens and sends it down a series of wires where it is processed electronically to produce the image we see on the television screen. And we can control many aspects of this image. Even the most basic TV set has controls for colour, brightness and contrast, and with more sophisticated processors we can do almost anything we want with the picture.

Similarly, our eyes and nervous system and brain together constitute a highly sophisticated information processing system that takes in the information from the light coming to the eyes and processes it to construct the image we ‘see’. But the light rays are not the only source of information that this process utilises. It also takes into account such things as our previous experiences and memories, our expectations of what we will see, the degree and focus of our attention and the purposes of our perception, and uses all this information to present to the mind an image of the world AS IF we were looking out the windows of our eyes. Or rather, AS IF we are looking out from a point mid-way between them on the bridge of our nose. Because although we have two eyes, we see only one image. Our binocular information processing system does enable our view to be three dimensional, making it more sophisticated than the two dimensional television screen, but it is still mediated, just as the television image is, in fact more so.

There are a number of things that need to be noted here. One is that although the picture we have of the world is a mental construct it had better be a pretty accurate one if we are going to survive in the world. Obviously from an evolutionary point of view there is a strong survival imperative in getting it more or less right.

More importantly it can be seen that there is no logical necessity that this is the only form in which our visual field might be presented to us. We are so used to seeing reality in this way that it seems like a given to us, but there are other ways the same information could be structured and presented. For example, we could see our environment as if looking down on it from above, like a map. This is precisely what radar does. Radar receives signals coming in to it from the environment around it, just like the human eye, but is designed to process them on to the screen in a map-like view. There is no logical reason why the human brain should not do the same thing – present the mind with a map-like image of its environment, just as a radar does. There may of course be very good adaptive reasons why the human perceptual system developed in the way it did, but I don’t know if anybody has ever tried to spell them out. The way we see the world may not be as inevitable as it seems.

In fact, seeing the world AS IF we are looking out from a single point is quite a sophisticated and complicated way of doing it. It requires very complex data processing. Consider the fact that, from the Palaeolithic cave paintings before 10,000BCE, through Egyptian and Greek and Medieval painting to the early fifteenth century, when the secrets of perspective drawing were discovered by the Florentines, the architect Filippo Brunelleschi and the painter Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Mone, nicknamed Masaccio, in Renaissance Italy, it took Western artists more than twelve thousand years to work out how to represent the visual field accurately on a two- dimensional surface. And this still has to be learned by human children. When children are young they draw a glass like this –

and the houses along a street like this:

Now in art education classes we were always told that this was because the children were drawing what they knew rather than what they saw. They knew the top of the glass was circular so that’s how they drew it and the bottom was flat (otherwise it would roll over) so they drew it flat. But what if this was actually how young children SAW a glass. What if the human perceptual system has to be trained, as visual artists have to be, in order to see the world from a single point in perspective? I don’t know if anybody has ever researched this possibility, or even how you would go about it.

Now the point of these speculations is to demonstrate that there is more than one way to visually represent an environment and that a perspective view is a highly complex, sophisticated way, compared to the relatively straight-forward map-like overhead view constructed by a radar. Which leads us back to OBEs – Out-of-Body Experiences.

They are most frequently reported as part of either a religious experience or a Near- Death Experience (NDE). English psychologist Susan Blackmore has suggested that OBEs occur during NDEs because when people are close to death the amount sensory input reaching the brain is limited. Moreover, the amount of blood and therefore of oxygen available to the human organism is extremely restricted and for survival needs to be concentrated on the life support organs of the body – the heart and lungs and so on. She has suggested that, in order to conserve energy, parts of the brain may reduce their activity and instead of trying to maintain the energy expensive construct of a perspective view of the environment, the brain may opt for the simpler less energy consuming map-like construct, thus giving the subject the feeling of being outside of their body looking down on themselves. So this unusual experience of seeming to be outside one’s body may be explained naturally in terms of the energy economics of a stressed physiological system – the brain organising things in a different way for a change – rather than being labelled as a supernatural occurrence.

And in the case of religious experiences, often they are also associated with significantly reduced mental and physiological activity, and from a psychological point of view, a subjective sense that the self is no longer separate from the rest of the universe but has dissolved into it. If there is no self to look out through the window of the eyes, it makes no sense to construct a world view AS IF a self is looking out. Thus a similar mechanism may occur but on a more cosmic scale. People involved in NDEs typically see the operating theatre, or the accident site from above. During my first mystical experience I felt I could see the whole of the world, perhaps even the universe, as if from a great height – I especially noticed Paris with the Eiffel Tower and Moscow, even though I had never been to either of those places. Other people have reported similar experiences as part of their mystic visions. So from a psychological point of view, both the slowing of brain activity and the loss of a sense of self typically accompanying religious experience would lead one to expect the experience of separation from the body, that does in fact occur.

Noetic quality of ‘religious experience

The third characteristic of these experiences that William James notes is what he calls their ‘noetic‘ quality. ‘Noetic’ comes from the ancient Greek word nohtoV [noËtos] = ‘perceptible, intelligible’, and has come to mean in English ‘of or pertaining to the mind or intellect; characterised by or consisting in intellectual activity’ [OED].

James claims that mystical experiences are noetic in the sense that they are states of knowledge, insight, awareness, revelation or illumination beyond the grasp of the intellect, for example an awareness of unity with the absolute, or of the immortality of the soul. But this seems to be a contradiction. How can they be both mental states characterised by/consisting in intellectual activity and states of knowledge beyond the intellect? Moreover this knowledge claim seems to beg the question raised by Radhakrishnan about the mediated content of all such experiences.

Nevertheless, the ‘noetic’ aspect of religious experience has been used to claim the experience gives us direct knowledge of God or at least of a spiritual realm. This involves drawing parallels between the phenomenology of religious experience and that of ordinary sensory experience and arguing by analogy that if the latter give us valid knowledge of the external world, the former must give us valid knowledge of the spiritual world. However, as we saw above, ordinary sensory perception is not in itself direct knowledge of anything – the world we see and hear is a construct of our brains and it is only knowledge to the extent that it meets other criteria – most especially what Douglas Gasking, my old philosophy Professor, used to call ‘the non-collusive agreement of independent observers’. If I think I see a physical object I can confirm it is really there by taking a number of steps: trying to see it from another angle, finding out if I can touch it as well, seeing if it’s still there next week, trying to do things with it and last but certainly not least asking other people if they can see it too. None of this is possible with religious experience.

This argument also falls down because although some aspects of the experiences may be very similar, as we have seen, there are also huge differences between them, especially with regard to content, to such an extent that they may be contradictory – if one is true then the other must be false and vice versa – so that religious experience in general cannot be counted as knowledge of anything. Of course the fact that they are contradictory does not mean that any particular experience is not direct knowledge of god, but that is a different argument. One cannot claim that religious experiences as a class are such direct experiences.

A second argument for the existence of god that is based on religious experience is inferential: It is argued that because religious experience is widespread, has a common phenomenological core and a common core of interpretation, these facts need explanation. It is concluded that the most plausible explanation is that god does in fact exist. However, as we shall see shortly, there is a respectable naturalistic explanation that may be just as, if not more plausible.

Transience of ‘religious’ experience

The fourth and final characteristic of religious experience noted by William James is its transiency. Mystical experiences tend to be fleeting in linear time – most last only a few seconds, some a few minutes. The problem this creates is that discussion of these experiences is almost exclusively discussion of the experiencers’ memories of them, not directly of the experiences themselves. If we are having a discussion about the aesthetic experience of looking at a painting such as Picasso’s “Weeping Woman” and there is any uncertainty we can actually go back to the National Gallery of Victoria and re- experience looking at it (assuming someone hasn’t run off with it again). But in considering mystical experiences we are relying almost entirely on people’s memories of these experiences, often recollected many years later. And we know that memory is a very unreliable instrument, because like our visual perceptions, our memories are constructs, and even more than perceptions they are affected by extrinsic factors and change over time.

1. When we recall events we forget or leave out parts of the experience in order to enhance its psychological meaning, at the expense of accuracy of recall. Memories change over time to produce a “better story”. We’ve all had the experience of slightly altering the events when we retell something that’s happened to us in order to make it a funnier, more interesting or more moving Well, our brains are doing this kind of thing unconsciously with our ‘memories’ all the time, re-constructing them to make them more meaningful and make them fit with our pre-existing beliefs and desires, and with our subsequent experiences.

2. Memory is even more susceptible to social influence and pressures than perception. Partly because such forces have longer to work on it. We have seen this recently with the phenomenon of False Memory Syndrome – people being induced through suggestion to believe things happened in their childhood that never actually occurred. The starkest example was the English woman in her twenties who became thoroughly convinced she had a previously suppressed memory of being raped by her father, but medical examination subsequently revealed that she was still a virgin.

3. One of the further dangerous aspects of relying on memory that recent research has brought out is that there is no correlation between the degree of confidence a person has in a memory and the accuracy of that Certainty is no guarantee of verisimilitude. The sincerity, determination or even obstinacy with which a person presents their memory of a religious experience cannot be taken as evidence for the exactness of their description, either of what happened or of how they reacted to it.

Let us examine more closely what happens when we have a mystical experience. In the first place there are a number of states or activities that can trigger such experiences, such as:

- fasting

- fever

- fatigue

- drugs

- over-breathing

- under-breathing

- excitement

- chanting

- dancing

- sensory deprivation.

All these physiological states can alter ordinary consciousness and allow unconscious feelings and images to rise into consciousness.

At a psychological level, as we change our mode of attention and put aside our usual conscious thoughts, for example by

- listening to music

- meditating

- experiencing some awe-inspiring, exhilarating aspect of nature (alpine crags, a storm at sea, the sky at night)

- being in a new, unusual and demanding environment.

then ecstatic feelings and images may emerge into our consciousness.

Deprivation, which is often carried to extremes in the quest for mystical enlightenment, typically leads to altered states of consciousness. Experiments in flotation tanks show that after many hours of sensory deprivation people experience complex, dynamic and often realistic hallucinations. This can also happen in real life situations – two miners who were trapped underground in total darkness for six days reported ‘seeing’ strange lights, doorways, marble stairs, a beautiful garden and, wait for it, women with radiant bodies.

Most if not all mystical experiences occur in extreme circumstances of some kind, either physiological or psychological (or even, in the case of some mass hallucinations, sociological). The visions and images and feelings that occur at this time can be understood in terms of the way we naturally respond to such abnormal situations, and do not need a supernatural explanation.

These visions and images are typically accompanied by a feeling of ecstasy. How do we explain this? Human (and animal) brains produce their own opiate-like drugs called endorphins that are synthesised in the brain and released into the cerebro-spinal fluid which bathes the cells of the brain and spinal cord. Endorphins have a variety of effects including analgesia [elimination of pain] and the inducement of intense pleasure, peace and calm. They can be released in various circumstances including stress, sickness, hypoxia (lack of oxygen, such as might occur during under-breathing or a meditative trance), hypoglycaemia (low blood sugar, such as might occur from fasting).

Endorphins can also set off seizures in the limbic system and the temporal lobe of the cortex and there is much evidence that unstable temporal lobe activity is associated with mystical experience. Although the exact mechanism may not be known, the immediate cause of the feeling of ecstasy in mystical experience is almost certainly the secretion of endorphins.

The self and the conscious mind

The mystical experience also involves a feeling of loss or dissipation of the self and integration or union with the universe. Because we view our Self with a capital S as a given, something essential, persisting and ‘REAL’, this experience seems bizarre. But once we realise that the ‘Self’, like our perceptions of the external world, is just another mental construct, the experience becomes less problematic.

Psychologists believe that newborn babies have no sense of self, and it is only after time and experience that they begin to distinguish between themselves and the rest of the environment, and the sense of self develops. But this is not a matter of gradually learning about a pre-existing entity. It is a matter of gradually constructing a mental model of ‘self’, facilitated, indeed encouraged, by the way we are brought up. The young learner of language discovers that she is allowed to say ‘I am drinking my milk’ but not ‘I am gurgling my tummy’. She has to learn to understand what people mean by ‘I didn’t mean to do that’ or ‘You shouldn’t have done that’. Systematically she is taught to use the words ‘I’, ‘me’ and ‘myself’ as though they referred to an autonomous and persistent thing. Humans learn to separate this self from its body, as though they were two different things and learn to attribute actions and choices to this thing. But it is purely a mental construct. There is in fact no physical or mental entity apart from this construct that is the self. Unlike our mental models of the world around us, there is no other reality that the concept of ‘self’ corresponds to or tries to model.

If this is the case, the feeling of loss of self and union with the absolute that occurs in mystical experience may be explained by the breakdown of this mental concept of ‘self’, which may occur through sensory deprivation, anoxia (lack of oxygen), or erratic temporal lobe activity brought on by the same sorts of conditions that created the other observed effects of mystical experiences.

The idea that self is a construct is a difficult idea for many people to accept. But it gets worse. There is experimental evidence that self-consciousness may be an irrelevant epi- phenomenon accompanying brain activity. Even when we think we, our Self, is doing something this may be an illusion. Most of us have had the experience of for example driving along a familiar route and when we get there realising that we have been totally unaware of the journey, because our minds have been elsewhere. Our bodies and brains have successfully negotiated some pretty complex tasks with out the assistance of a conscious ‘self’.

Consider these two experiments carried out by Californian neuroscientist, Benjamin Libet.

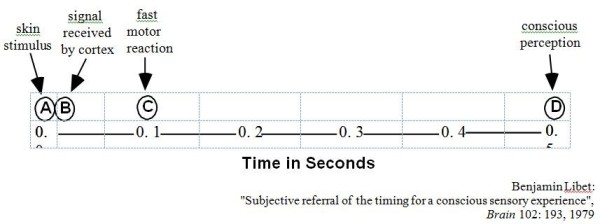

1. In the first, Libet gave subjects a tactile stimulus and measured the time of their reaction and their conscious perception of that His findings were surprising:

A touch on the skin occurred at A and was signalled to the cortex at B. At C the subject reacted, for example, by pressing a button. However the subject was not conscious of the sensation nor of his own reaction until the instant marked D. Nevertheless the subjects felt that C was a conscious act.

2. In the second experiment, subjects in the laboratory were asked to it around and to take their time and to flex their wrists whenever they wanted to. EEG electrodes were used to measure the brain activity associated with this decision. They were also asked to note the precise time they made their decision to act. Libet then timed the three events – the decision, the brain activity and the flexing – and found that the conscious decision to act actually came after the start of the brain activity that produced the In other words, the brain was ‘acting’ before the conscious decision to act was made.

So not only is the self an illusion, perhaps the self-consciousness that constructed the concept of self is an irrelevance. But if so, why are we conscious? What is the evolutionary survival value if it is a kind of theatrical afterthought to otherwise seemingly self-sufficient physiological processes? What is the adaptive purpose of consciousness? Perhaps there is none. Some features of an organism can exist as the harmless by-products of evolutionary adaptations for other purposes. We humans find ourselves in possession of an entire collection of abilities that have no obvious selective advantage. Few people have had more children because they could solve differential equations or play chess blindfolded.

Memes

A recent explanation for the development of the conscious mind has arisen out of Richard Dawkins’ proposal, in his book The Selfish Gene, of the concept of the ‘meme’. The meme is a unit of culture, spread by imitation, such as at the simplest level wearing a baseball hat back-to-front. Ideas, habits, skills, behaviours, inventions, songs, and stories are all memes. Memes, like genes, are replicators. In her new book, The Meme Machine, Susan Blackmore argues that we are all the products of our memes just as we are the products of our genes, but memes, like genes, care only for their own propagation. Memes, according to Blackmore, “are stored in human brains (or books or inventions) and passed on by imitation”. They can pass vertically, as from parent to child, but – unlike genes – they can also pass horizontally in peer groups and obliquely as from uncle to niece. Each of us is a meme machine. Over the years memes have proliferated in such numbers that individuals, competing to imitate the best imitators, needed bigger and bigger brains to contain the flood. Now human heads are so big they barely squeeze through the birth canal.

The theory of memes as self replicating ideas in the substrata of human minds, co- existing with self replicating genes in the substrata of human bodies, explains many baffling phenomena of life, from seemingly irrational religious beliefs through to why people are altruistic and to which pop tunes, films, and toys sales at Christmas are the most successful. For example, our proclivity for recreational sex (which if we take proper precautions does not allow us to spread our genes) is explained by Blackmore as a means of attracting partners who will spread our memes. Blackmore makes a compelling case that our inner self, the ‘inner me’, is an illusion, a creation of the memes for the sake of their own replication. According to this view, we are nothing more than machines for spreading memes.

Conclusion

If the characteristics of mystical experiences can be understood in the above ways, is there then no value or significance in them? Of course there is. To explain something is not necessarily to explain it away.

To take a parallel example, the fact that we now know a great deal about the physiology and psychology of human sexuality does not detract one iota from the wonderful experience of falling in love. We do not say that love is no longer important or valuable or worth giving or receiving, worth striving for and even dying for, simply because we now understand it better. Knowing that it’s all ‘just chemistry’ doesn’t stop the chemistry from functioning, often in a quite overwhelming way.

Mystical experiences are intrinsically worth having for the feelings of ecstasy and connectedness they involve. I know of no-one who regrets having such an experience nor anyone who wouldn’t want to have the experience again if this was possible.

Moreover, the experiences seem to have a uniformly beneficial effect on people’s subsequent lives. The fact that they involve a sense of oneness and union with the rest of the universe can only have positive outcomes for the peace and ecology of the planet. They seem to focus and concentrate our feelings of awe about the vastness and mystery of the universe, but without alienating us from it, because at the same time they underline and emphasise our own essential place in it.

And, if we can get beyond their cultural accretions, the familiar and learnt images we usually dress the experiences in, and pay attention to their core significance, they may teach us a very important basic truth about ourselves, that is, that self is a mental construct. In a sense, an illusion. Perhaps a useful illusion, but an illusion none the less. And knowing the self is a mental construct can have profound beneficial effects on the way you lead your life.

Organised religions have always had an uneasy relationship with mystics, at worst persecuting them and at best trying to shoe-horn their experiences into pre-existing sets of religious beliefs. But if such experiences are to become simply adjuncts to the creeds and rituals of entrenched religious hierarchies, what is the point or value in them? An atheist, approaching the mystical without this religious baggage, has perhaps a better chance of making it a life-enhancing and life-changing experience.

To radically misquote Karl Marx, religions have merely interpreted the mystical experience in terms of their various dogmas; the point is, to be changed by it.

Further reading:

Susan Blackmore. Dying to Live: Science and the Near-Death Experience.

Susan Blackmore [with an Introduction by Richard Dawkins]. The Meme Machine.

Fraser Boa. The Way of Myth: Talking with Joseph Campbell.

Joseph Campbell. The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor as Myth and Religion.

R. L. Gregory. Eye and Brain.

F. C. Happold. Mysticism: A Study and an Anthology.

Elizabeth Loftus. Memory.

Andrew Neher. The Psychology of Transcendence.

Graham Reed. The Psychology of Anomalous Experience.

Alan W. Watts. This is IT and Other Essays on Zen and Spiritual Experience.

John White [ed]. The Highest State of Consciousness.

Ken Wilber: The Marriage of Sense and Soul: Integrating Science and Religion.