Unlike psychologists, psychiatrists and other medical practitioners who offer treatments for mental illness, Scientology escapes regulation because it offers services as a religion.

Despite the efforts of Senator Nick Xenophon, who unsuccessfully attempted to link Scientology’s tax free status to providing services which are beneficial to the public in 2010, there is currently no regulation of deeply worrying practices occurring in broad daylight in the centre of Sydney’s CBD.

The RSA believes state and federal governments should ensure the provision of health services are regulated by professional bodies regardless of what sort of organisation provides them.

RSA board member Hugh Harris writes of his introduction to Scientology.

Stepping inside Scientology’s Castlereagh Street headquarters in Sydney, with its images of erupting volcanoes and Star-Trek-style video pods, I feel like I’d been transported back into the realm of 1960’s science-fiction.

Waist-coated attendants zip back and forth.

Soon, I’m looking down at Scientology’s Oxford Capacity Analysis personality test: 200 often strangely worded questions, asking how I “feel RIGHT NOW” about a disparate range of issues.

“Does an unexpected action cause your muscles to twitch? ”

“Do some noises ‘set your teeth on edge’?”

“Do you browse through railway timetables, directories or dictionaries just for fun?”

“No,” I answer, to all of these.

Pondering whether I “enjoy telling people the latest scandal about my associates”, I’m distracted by the roped-off office of church founder, the late L. Ron Hubbard. Presumably, the great man beams in from out-of-galaxy from time to time.

Suddenly, a young man is talking.

“Hi, I’m Scott*, come and let’s check out your results,” he says.

“This graph indicates what you have told us about yourself” he says, reciting the standard preamble. “These results are not my opinion, but a factual, scientific analysis of your answers.”

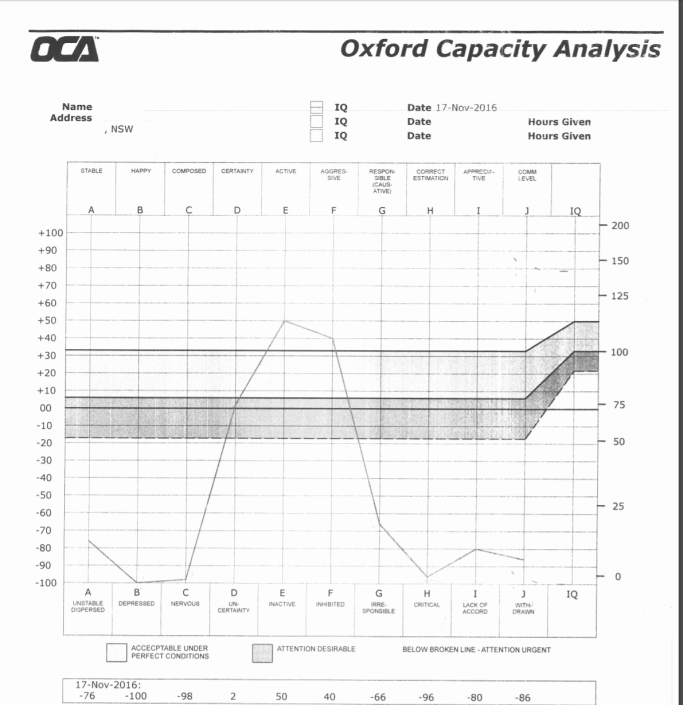

Pinpointing scores on a scale from -100 to +100 for ten personality traits, including items like ‘Stable’, ‘Happy’, and ‘Composed’, the graph divides them into regions for ‘Normal’, ‘Desirable State’ or ‘Unacceptable State’.

My graph was disturbing to say the least: a mostly submerged iceberg, with only the tip rising above ‘Unacceptable’.

Staggeringly, I scored the lowest possible -100 for ‘Depressed’, along with dire scores for ‘Nervous’, ‘Critical’, and ‘Withdrawn’.

At first I laughed in surprise and embarrassment. Apparently, I am the most depressed person in the world.

But then, I recalled giving answers suggesting that I’m not depressed at all: answers indicating that I’m generally happy, I often sing or whistle just for the fun of it, I sleep well, I find it easy to relax, and I cope with the everyday problems of living quite well.

How did these answers fail to improve my worst-possible score for depression?

Scott said the analysis is a complex reading of all my answers.

“What this shows is there’s something on your mind. You’ve got some problems in your life, right now.”

“Have you had any breakups, or loss?”

Sure, I said, but haven’t most people?

Noticing Scott reading from a printout, I asked if I could see it.

One after another, the page was filled with blunt, judgmental observations (my emphasis).

“You see no real reasons to live as your life is full of problems and difficulties that your despondent attitude prevents you from solving”.

“You are completely irresponsible.”

“You are very irritable and can become hysterical or violent in your actions.”

And so on. No longer was I laughing.

Recommending urgent treatment in Scientology’s Dianetics program, Scott brought out the books and the DVD’s.

I stopped him there. Explaining to Scott that he could put it down to my critical nature, but I simply didn’t accept the report’s findings.

Jokingly, Scott pointed to me -96 score for ‘Critical.’ We both laughed.

Scott gave me a copy of the printout, shook my hand, and then let me loose on central Sydney.

Seemingly, the personality test is calibrated to generally produce an alarming result. L. Ron Hubbard advocated reinforcing the ‘ruin’ of the subject’s personality, followed by advice on salvaging it by using Scientology. Regarded as manipulative and unethical by many psychology organisations, the test is not scientifically recognised, nor has it been substantiated using standard psychological methods.

As I left the Sydney building, I noticed some uni students in the lobby. I wonder how I’d have reacted to such a damning character assessment at such an impressionable age.

After a Daily Mail reporter undertook the test in 2003, she said felt like “curling up in a ball and never going out again.”

Only a few hours after taking the test in 2008, Norwegian student Kaja Bordevich Ballo, took her own life by jumping from her 4th-storey dorm room window. Despite leaving a suicide note for her family apologising for not “being good at anything”, the resulting police investigation failed to confirm a causative link to Scientology.

Still, looking at these smiling young faces, I want to tell them to get out of here.

After kidnapping his wife in 1951, L. Ron Hubbard was reportedly diagnosed as paranoid schizophrenic. This may explain Scientology’s hostility to the field of psychiatry, which it describes as “an industry of death”, and why the church spurns psychiatric drugs in favour of vitamin supplements, and spiritual practices.

The ramping up of advertising for free personality tests coincides with the recent opening of a $57 million ‘Scientific Wonderland’ in Chatswood, NSW, where Scientology will treat people with mental issues caused by depression, substance abuse and trauma.

Despite diagnosing and treating mental illness, Scientology escapes the regulation of health authorities because it offers its services under the guise of religion. That’s how it continues to get away with claiming its services are “factual”, and “scientific” without proper scrutiny. Surely, this is a loophole which needs closing.

*names have been changed.