Some, like Barney Zwartz (Senior Fellow of the Centre for Public Christianity), are of the opinion that there can be no basis for morality without religion. For example, in the web site he says that the claim in the Humanist Manifesto that morals can be developed from science is another fantasy.

Philosopher Sam Harris hopes otherwise, and in his book The Moral Landscape – How science can determine human values he raises the topic, stating that: “The goal of this book is to begin a conversation about how moral truth can be understood in the context of science”. He then defines ‘moral truth’ as the ‘connection between how we think and behave and our well-being’.

Harris bases much of his work there on the notion of well-being. He does not define well-being, and sees no need to do so. The graphic example he considers of two hypothetical lives: one disastrous and one that is anything but, suffice to illustrate his case (pages 13-14). Harris also contends that: “human well-being entirely depends on events in the world and on states of the human brain. Consequently, there must be scientific truths to be known about it.”

Harris does not attempt to produce the science he requires. This note seeks to continue Harris’s conversation, to explore some of the topic, and consider what rational or scientific basis there might be for certain sorts of behaviour and what would be the consequences for well-being.

The topic of cooperation has been widely investigated, notably by Robert Axelrod in his book The Evolution of Cooperation. Cooperation typically provides a benefit to both parties, often at the same time, and so is different from ethical behaviour which may, on the face of it, seek no reward.

Another discussion in Wired magazine, ‘The Science of Charity’ observes that “the first thing to note about giving away money is that it feels really good”. It then contends that altruism “is not a superior moral faculty that suppresses basic selfish urges; rather, it is hard-wired in the brain and pleasurable.” This raises a motivation that seems only derivative. If there is release of a dopamine/oxytocin reward for acts of charity, it seems likely it would have evolved as a consequence of some value in the outcome, rather than as a standard feature of the natural world.

It might well be that charity worked in early human societies, and that evolution selected for those who lived in such societies. A mutation that gave a chemical reward would have been helpful, but would follow from the successful experiment in social conduct, and would not be the initial cause of the behaviour.

For a scientific basis for morality, we need the hypothesis that such behaviour, if adopted by enough of the population, improves the well-being of that population. And hence provides a reward of some sort for the members of that community.

In looking for a scientific basis for human values there is a conundrum, identified by James and Stuart Rachels’ criticism of Hobbes’s social contract theory in The Elements of Moral Philosophy (9th edition). The word ‘scientific’ implies something rational, and that there should then be a benefit of some sort to morality – which seems at odds with the usual notion of ethical behaviour. From the same source we have: “Some individuals cannot benefit us … we may ignore their interests … [this] implication of the theory is unacceptable.” However, that statement seems to assume that there is already a basis for moral duty and what is then acceptable and that it relates only to individuals and not a community.

Harris considers that: “’better’ must still refer … to positive changes in the experience of sentient creatures.” (page 37). This note considers only interaction with humans, and leaves the development of a system of treatment of other life forms to a process that can only be analogous, and might lack a scientific basis of its own.

Prehistory Many have written about an assumed sharing of resources in early cultures. It is generally accepted that cooperation, and especially food sharing, are essential for survival in a hunting-and-gathering economy. “Without food sharing to mitigate the day-to-day shortfalls in foraging [humans] could simply not survive,” one analysis argues. Similar cooperation exists amongst some animal groups. Where the community was a small one, and where success in hunting (and perhaps gathering) was uncertain, it would make sense to pool resources. The ethics of sharing would be plain – if we share, we do as well on average, and might miss the peril of a few bad days in a row. For modern societies, where we may often meet people with whom we have little or no connection, and whose fate we do not share, a different set of circumstances applies. As in the hunter-gatherer case, we seek a concept of practice that, if it were set in the culture, it would likewise provide a benefit or protection from disaster even when the provider might be a stranger.

We have the ‘Golden Rule’ from a number of philosophies: ‘do unto others as you would have them do unto you’, and its reciprocal: ‘do not do to others what you would not want them to do to you’. This suggests two approaches to the problem, one which provides for initiative and one for restraint. The former is in the broad category of charity, and the latter covers matters ranging from courtesy through to crime. According to the Harris hypothesis, a science of morality would need to show how charity is in the best interests of all, and how prevention of bad behaviour improves well-being for the community.

The latter case may be easier to deal with. Certain acts seem deplored in all societies, murder and lying being two examples. Being attacked in any form will often provoke a response provided there is capacity to do so. The situation for wildlife was explored by J. Maynard Smith and G.R. Price in ‘The logic of animal conflict’ (Nature, 1973). The conclusion was that a ‘retaliator’ model of behaviour was stable in some sense compared with such alternatives as unrestrained aggression or constant submission. Whilst the conclusions depend on the assumed payoffs, they are considered “biologically sound” (The price of altruism by Oren Harman, p266). Hence there is science to this and perhaps some relevance to interactions between individuals.

For societies such as the nation-state laws provide for protection against aggression, with the level of protection constrained by the nature of the government and its capacity to enforce its laws. For there to be a scientific basis to support the contention that this improves well-being for the community, it would suffice to show that the bulk of society does better to employ a guardian than to attempt an equivalent of a series of armed individuals or gangs. This is just the equivalent of the economic principle of comparative advantage.

It remains then to consider charity. It provides a service that is offered, rather than preventing harm, which is otherwise forced upon us.

Charitable actions The parable of the Good Samaritan has been widely used to illustrate the actions a Christian might take, and it might be useful for our purpose here. One form of the relevant text is in Luke 10:25-37:

“… Jesus said: “A man was going down from Jerusalem to Jericho, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him of his clothes, beat him and went away, leaving him half dead. A priest happened to be going down the same road, and when he saw the man, he passed by on the other side. So too, a Levite, when he came to the place and saw him, passed by on the other side. But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him. He went to him and bandaged his wounds, pouring on oil and wine. Then he put the man on his own donkey, brought him to an inn and took care of him. The next day he took out two denarii and gave them to the innkeeper. ‘Look after him,’ he said, ‘and when I return, I will reimburse you for any extra expense you may have.”

We may draw some inferences here, though not all of them are necessarily intended by the author of the parable:

- Obviously, being left ‘half dead’ implies serious damage, and perhaps that the victim would not survive without help.

- The Samaritan is not known to the victim, and is certainly not a relative or friend.

- The Samaritan does not seek, nor have any expectation of, recovery of the amounts expended. If he is to have any comparable service when in need, it would be at a future place and time, and provided by someone else.

- Whilst the generosity of the Samaritan is notable, the perceived value of the benefit to the recipient, from his point of view, was much greater than the cost incurred by the Samaritan. The Samaritan offered some first aid, and a night’s accommodation; the victim might have had his life saved.

There will be many cases where the value of a service rendered is of much greater value to the recipient than financial values alone would imply. A society in which this behaviour would be regarded as appropriate would plainly have benefits for the society as a whole. In extreme cases such as being left half dead, it would provide for some survivals. In less dramatic situations there is still an improvement to well-being. Any loss to the donor is remedied in a statistical sense, in that there is then some possibility of assistance when it is required, even from a stranger.

It is then necessary to consider the relationship of the cost of a service to the benefit it provides. Recently, I lost my phone in a park but discovered this only after returning home. On calling the number a woman replied that she had taken the phone to a police station, but it was closed, so she still had the phone, which I was then able to recover from her.

Why did she provide that service? She asked for no reward, and the box of chocolates I chose to give her was in no way comparable to the impact on me of having to replace the phone and all it contained. Hobbes social contract notion is relevant here. An attempt at precision in calculating values here seems idle. There are too many unknowns: her time-cost, my costs of replacement, time, and inconvenience. However, drawing perhaps by analogy with Harris’s statement that “our inability to answer a question says nothing about whether the question itself has an answer” we might attempt an answer in a way that lacks precision but might still be convincing.

We might seek some mathematical calculation in relation to the examples. If our conclusion is that there is not, and cannot be, any science it could be because we would despair of getting plausible estimates of either probabilities of services, or the value of such services to the parties receiving or providing.

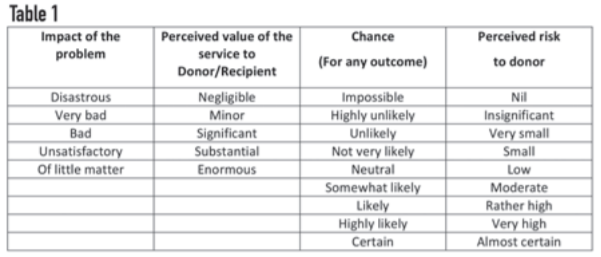

An alternative, which might be sufficient as a basis for action, would need to consider values that are unknown but whose relativities can be assessed. Such relativities can be ordered, and further, have some degree of magnitude assigned. A rough attempt might be, for example, as set out below (Table 1):

– On the basis of which we do a calculation with values but not numbers. The algebra of such a system would be limited without assigning numerical values, and any such values would be difficult to justify.

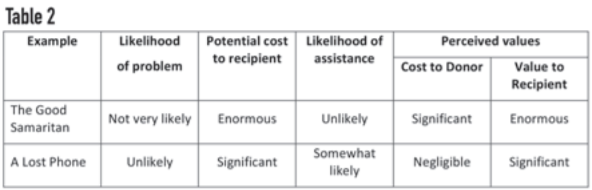

For our two cases, we might have (Table 2):

There might not be a scientific basis on which to assess likelihoods. For well-being to be improved, it suffices to establish that the action, if performed, improves wellbeing. Many charitable actions require no more of the donor than to decide how much, and what kind, of service to provide. Some will involve some risk, for example it we seek to assist someone in danger as when fire fighters attempt to save lives at risk. In such cases there could also be doubt about whether the planned action would succeed.

The statistical expectation equation is derived from measuring the likelihood of success, the value to the recipient minus the risk to the donor, and the cost to the donor. Well-being is not increased if the value is negative. It is notable that, even amongst Christians, this sort of calculation is carried out. Whilst they are advised: “Go, sell everything you have and give to the poor” it would appear that very few do so.

We could deduce that if society accepts that its members offer service when that service is within capacity such that there is an expectation that well-being is increased on a relative basis, it provides the expectation of improved well-being to the community in general. And hence, on balance, to its members. Of course, such expectations can be disappointed, with consequential breakdown of ‘the contract’.

This exercise is plainly, at best, a broad-brush approach to the topic. Any conclusions would only be drawn in similarly broad terms – that if moral behaviour is to be rational, there must be a payoff of some sort and that the value of that payoff and its likelihood depend on the circumstances, and will be difficult, if not impossible, to quantify in numerical terms.

We would conclude from the table that net well-being is increased, since the values to the recipient of the charitable behaviour are greater than the costs to the donor. As a corollary we could suggest that, were the values reversed, the service would not take place. We would not waste much time or expense on a trivial matter.

The issue of ‘sentient beings’ is unresolved. It might be that the treatment of non-human life forms would be dealt with by extension so that the principles that apply to humans would then apply to how we treat other sentient beings. In Australian society, we may engage in behaviour that would seem to have no chance of providing a tangible benefit to the provider. We might deplore cruelty to animals but the sheep we save from the perils of live transport, or the birds we release from cages, will not reward us in any material way.

The Oxford dictionary provides a meaning of sentient as: ‘able to perceive or feel things’. To that topic we might consider such matters as Jack the baboon who assisted a disabled railway worker in a wide range of his duties, including the actual signalling, as described in Simon Morris’ Life’s solution (p242). Or there is the notion that a plant’s root system acts like a brain (the ‘root-brain’ hypothesis of Charles and Francis Darwin). I leave it to the reader to sort out what ethical treatment should apply to cases of non-human sentient beings.

– Hugh Sarjeant has qualifications in mathematics, statistics and computing, and has spent 40 years in working in the actuarial field in both public and private employment.